Sometimes, it feels like there exist mysteriously magical places on Earth that share a special kind of geo-karma. Locations on this glorious planet whose extremes of pristine whisper a certain ethos of sacred responsibility, a soul-level compulsion to protect and preserve. It’s something I have observed having married Arron (Wild Alaskan Company’s founder + CEO), who hails from a multi-generational commercial salmon fishing family in Alaska. For Arron’s family, Alaska isn’t just their home — it’s their duty.

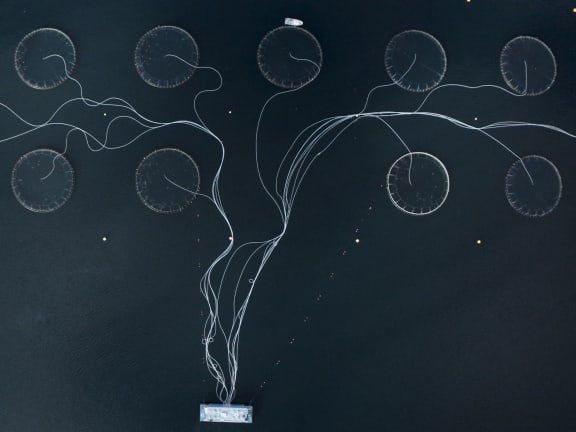

So, when I had the pleasure of seeing Patagonia’s latest film — Laxaþjóð | A Salmon Nation, which you can watch here — about the imminent dangers of open-net salmon farming in Iceland, I immediately understood the monumental conundrum the country faces. On the one hand, there are — like in Alaska — individuals whose reverence for their homeland is not negotiable. On the other hand, Icelanders are faced with outside influences that threaten their homeland’s natural balance. The crux of this contention serves as a cautionary tale for what can happen if measures to protect our natural environment are not taken seriously and immediately. With the prevalence of open-net salmon farms in Iceland for the singular purpose of breeding salmon to grow as fat as possible in the shortest amount of time and for the highest profit — and little to no regard for the cascade of negative effects that come with this plight — the result is what one of the subjects of the film aptly, and powerfully, refers to as “man-made pollution.”

The film — which I found to be as gorgeous as it was insightful — weaves together deeply emotional perspectives from scientists, fishers, environmentalists, ecologists, protesters and passionate Icelanders about the import of wild salmon stocks in Iceland, the priceless value of their home rivers, and the irreversible damage imposed onto both as open-net fish farming expands in Iceland.

As I watched the documentary, I could not help but think of Alaska, my husband’s home state, which, unlike Iceland, completely outlawed commercial finfish farming in 1990. "Salmon farming began in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s,” the Alaska Department of Fish and Game's website explains. At the same time, Alaska considered allowing the farming of finfish; however, by 1990, it concluded that the dangers were too great to the wild system that Alaska depends upon. The farming of finfish in Alaska was banned in 1990 to protect wild stocks from the danger of disease and pollution as well as the possibility of escaped farmed fish displacing or breeding with wild fish. Alaska statutes currently prohibit any species of finfish farming in the waters of the state.

And even before Alaska was a state, the people who fell in love with the majestic glory of its land and seas were fighting to protect them. My husband’s own grandfather, Robert C. Kallenberg, pioneered the family’s destiny by moving there in 1926, where he began commercial fishing for wild sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay on a wooden sailboat. Such was his passion to understand and protect the salmon species that he earned a master's degree from Cornell University, publishing a thesis titled "A Study of the Red Salmon of Bristol Bay with Particular Reference to Teaching its Conservation." He would also serve on Alaska’s Territorial Board of Fisheries and pass on his wisdom to anyone who would listen. Grandpa Kallenberg wasn’t only intent on studying and understanding the conservation of wild sockeye, but just as urgently, to codify his learnings so that they would be teachable to future generations.

Patagonia’s film explains that in 2024 the Icelandic government will also have the unique opportunity to transform the conversation about open-net salmon farming across Europe. We know that Iceland has already allowed commercial salmon farming in its waters, but they are witnessing firsthand the damage it is causing — which means that this is a critical moment in time for the people of Iceland: they can, hopefully, reverse this damage and rewrite the rules, and perhaps take its cues from Alaska, which is today the world’s gold standard when it comes to fishing sustainably. We can look at Iceland and learn from its past mistakes — but hopefully also about the power of course-correcting and, as such, lead the way forward.

Together, all the subjects in the film make an incredible and incontestable case for the urgent need to not only shut down the current salmon farms in Iceland just as Alaska has done but also ban its practice moving forward. Each voice in the piece exemplifies universal truths about Iceland and its wild salmon: that they are inextricably linked. That the salmon are part and parcel of the place’s soul. That the fish’s habitats and journeys are as much a part of the place’s identity as are its own people.

All of which, of course, again brings me back to Alaska. Here are two places endowed with a resource that, left to its own natural determination, could exist in a state of perfect harmony with its world. Two places endowed with the unique opportunity to show the world how to care for itself.

I cannot say enough about how powerful, moving, important, and illuminating Laxaþjóð | A Salmon Nation is. It is more than a film — it’s a testimony. Thank you, Iceland. And thank you, Patagonia, for always holding fast to what matters the most.

Live Wild!

Monica

Pictured above: An aerial shot of open net salmon farms. Still image from A Salmon Nation courtesy of Patagonia.